I jumped back into serious Greek study about two weeks ago.

As I mentioned in my last post, I’ve committed myself to learning Modern Greek to conversational fluency this year while also reviving and mastering Koine Greek.

Koine Greek is an ancient (approx. 300 BC to 300 AD) ancestor to today’s Greek and a language that I spent 4 years on in college but never quite completed.

It’s always bugged me as I’ve never liked leaving things incomplete! 🙂

This past two weeks has really been an eye-opener for me as to how much I truly remember.

And how much I’ve forgotten.

As I’ve said before, if you learn a language properly the first time then you never forget it. This is why I believe that if you learned a language in school but can’t remember it, it means you never really learned it in the first place.

I can already see those aspects of Koine Greek that are etched into my memory forever.

And other parts that I must have not learned properly as I’ve completely forgotten them.

Today I’ve been reflecting on my initial struggles with Greek way back in college and also the common points of confusion that my peers had when starting the language.

I’m going to share some of that with you.

One of my main goals with this project is to identify the points where Koine Greek is a major struggle, look at how it’s commonly taught and see if I can find a way to radically improve it.

UPDATE: If you’re looking for a high quality online Biblical Greek course/resource, then I absolutely recommend Biblingo.

The problem with the way Koine Greek is taught

I’ve been reflecting on this for a long time:

What’s wrong with the way most colleges (and resources) teach Koine Greek?

I was poring over highly respected Greek textbooks like The Elements of New Testament Greek by Duff and Wenham, and Basics of Biblical Greek by William Mounce which go into great detail on all the fundamental aspects of Koine grammar and I kept asking myself:

How could this be better taught?

I’ve seen a whole class fail Greek.

Just hearing terms like optative mood, second Aorist middle and periphrastic tenses is enough to make a student drop out of Greek and give up altogether.

But the reality is that learning these things is unavoidable and necessary.

This is especially true with Koine where an incorrect verb tense can have enormous theological ramifications.

If you think of the difference in English between “I have stolen money” and “I stole money” – it’s not just a small grammatical difference. Saying “I stole money” sounds a lot more serious and recent – like a confession of something you’ve just done. “I have stolen money” on the other hand could have happened years ago and you’re just recalling it as a past experience.

So when translating Koine Greek, we can’t escape the fact that the grammar is truly important to learn.

But…

The question in my mind is when and how.

It’s at this point that I want to present a challenge to every NT Greek student (and teacher):

I think the way that Koine is traditionally taught is backward and a lot more tedious than it needs to be.

With modern languages, we don’t start off by learning how to become a translator like we do with ancient languages like Koine.

Imagine walking into your first French lesson and being handed a curriculum for advanced French translation on day one:

“By Week 12 of this term, we’ll be translating the philosophy of Jacque Derrida.”

That’s essentially what we do with NT Greek courses.

We expect students to go from zero knowledge of a language to translating deep, abstract theological concepts in the New Testament within a few short months of study.

The more I think about it, the more I realize just how completely unrealistic this is.

You certainly wouldn’t see this in any modern language course.

As I’ve said before, in order to become a translator you need to first know a language.

It doesn’t happen the other way round.

NT Greek classes today don’t teach the language as a once living, natural language – instead classes are more like code-breaking sessions where you learn the appropriate rules and then proceed to crack the text.

It’s almost expected that you’ll forever rely on a lexicon, grammar tables and commentaries in order to use Greek.

In other words: never actually learn the language.

You learn the alphabet, some core vocabulary and enough familiarity to navigate a lexicon.

But imagine being able to pick up a Greek New Testament, read a Pauline letter fluently and actually hear the human who wrote this – hear and get a feel for the human creativity behind all the little nuances, words and expressions the author used.

But can you treat a dead language like it’s still alive?

So the big question is:

How does someone learn a dead language as if it’s still alive?

How do we avoid treating Koine Greek like a code-breaking exercise?

If you’ve followed me for a long enough time then you’re probably already familiar with how I approach modern languages.

Over the past few years of running this blog, I’ve been able to achieve conversational fluency in languages like Russian, Korean and Irish with virtually no grammar study.

Languages with a reputation for “hard” grammar.

I achieved this through a method I call chunking which I developed on the back of Michael Lewis’ Lexical Approach (an ESL methodology).

I stand by my belief that you do not need to study grammar in order to learn to speak a foreign language. I’m living, walking proof that this is accurate.

To sum up how this works very briefly, languages are not just a system of rules to be memorized.

Languages work as a stack of building blocks.

We take words, collocations, phrases and sentences that we’ve heard countless times throughout our lives and we piece them together like blocks – almost everything we say in our first language is completely unoriginal.

You may think the sentences you’re speaking are original but in fact all you’re doing is borrowing from what you’ve already heard (or read).

You’ve encountered it all before.

When you speak, you’re piecing together chunks of language that you’ve heard thousands of times throughout your life. Those chunks become so totally familiar to us that we speak them without even thinking about it.

It becomes a habit.

That’s also why it’s so easy for a native speaker to spot a non-native speaker (apart from accent).

As native speakers, we’ve learned to plug the right pieces into the right places according to what we’ve heard countless times, whereas a non-native speaker attempts to put pieces where they don’t fit based on assumptions (because they haven’t had the same length of exposure that we have).

Or, like most Koine Greek students, they try to align everything with the grammatical rules they’ve learned – rules that are often broken in natural speech.

Chunking is about letting go.

Letting go of the “need” to know how everything works at once and instead just letting exposure and repetition do the work for us.

I’m attempting to apply this to Koine Greek.

Looking for the patterns in Greek

As I said above, knowing Koine Greek grammar well is unavoidable and something you’ll gradually have to learn if you take theology seriously.

Small nuances of meaning can have a major impact on what people believe.

So I’m not suggesting we abandon grammar or even suggesting that it’s possible in the case of a language that’s no longer spoken.

The goal with what I’m doing is to work on acquiring proficiency through frequent exposure to high-frequency chunks (whether they be particular word forms, collocations or phrases).

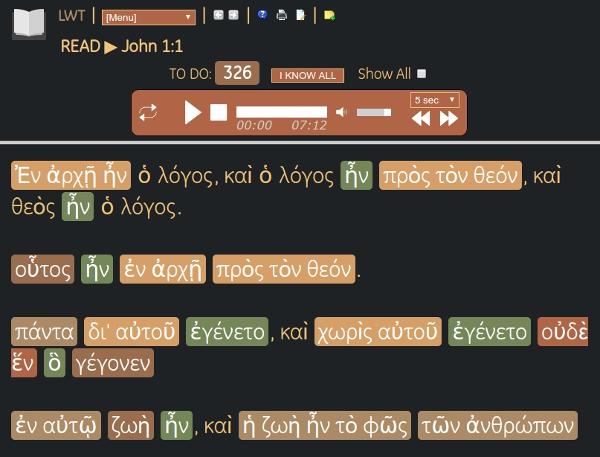

Look here:

Just looking at this first passage of John (a simple example to begin with), you see that I’ve begun to highlight (using LWT) what I call “chunks”.

These are the kind of high-frequency patterns I’m focused on:

Ἐν ἀρχῇ – in the beginning

πρὸς τὸν θεόν – with God

τῶν ἀνθρώπων – of men

δι’ αὐτοῦ – through him

χωρὶς αὐτοῦ – apart from him

ἐν αὐτῷ – in him

But it goes much further than that.

Pay attention to frequent patterns of placement of words like ἦν and ἐγένετο. There’s a predictable flow and pattern to the way everything’s spoken/written (same reason we say “knives and forks” and not “forks and knives” in English – it all has to do with natural, phonetic flow).

As I’ve said before in posts where I’ve talked about chunking, you may think that you’re only learning a few lines of text.

Isn’t it a waste of time memorizing half a dozen lines of a passage?

No.

These few simple lines will enable you to recognize patterns in a multitude of other instances (I explained this here) – especially when it’s the same author.

I’ve listened to this native (Modern Greek) audio of these few lines literally hundreds of times in the last few days (probably driving my wife crazy playing on repeat!).

I’ll continue to listen to this another thousand times until it rolls off my tongue like English does.

Even though the pronunciation difference between Koine and Modern Greek is undoubtedly very different, I’m using these native recordings daily for repetitive listening (it also helps me practise my Modern Greek pronunciation).

Note: If you asked me what verb tense or declension so-and-so is, I probably couldn’t name it for you at this stage – but I couldn’t do it in English either to be honest.

I look at a word or construction and say:

“I don’t need to know why that is what it is yet. The rules behind that construction don’t matter right now.”

“All I need to know is that X means Y.”

Treating the language as a living language (although dead) and hearing the author’s voice as I read.

Frequency is key.

FYI: I’m using the Modern Greek reading of the Koine text that I found on Vivlos. For clarifying terms and inputing them into LWT, I refer to GreekBible.com.

I’ll be going into greater detail about the method I’m using soon and will have some useful video content on my YouTube channel to follow.

Curious about effective grammar study methods for Koine Greek? I’ll cover that in an upcoming post.

🎓 Cite article

Grab the link to this article

Grab the link to this article![Black Friday (2025) Huge Language Learning Deals [+ Gift Ideas]](/.netlify/images?url=_astro%2Flanguage-learning-gifts.B3xs8tp4.jpg&w=270&h=152&q=50)

37 COMMENTS

NO ADVERTISING. Links will be automatically flagged for moderation.

William Gentile

Thanks for sharing your language journey in Greek. I happily stumbled on your most interesting posting/blog. May you continue to learn and bless others with that knowledge. The LORD appears to be ‘lifting the curtain’ in many areas, long concealed or forgotten and buried! ...”and knowledge shall be GREATLY INCREASED”, is now becoming an understatement in our age. Making us say “What’s next Papa?!”

Again I very much enjoyed your very well presented article, especially the audio clip of John 1:1! Shalom and Greetings, and “perhaps next year in Jerusalem” .

Kind Regards, from Brother William, the Gentile

Avery

I’d really like to find a way to learn Koine Greek and commit myself to it. What would be your first recommendations?

Jim Henderson

Good points.

A great way to learn Koine Greek is the audoivisual course “Living Koine Greek for Everyone”

https://www.biblicallanguagecenter.com/greek-first-lesson/

Try the demo first lesson free.

It brought my moribund gk to life!

David Pimental

Great post. While I think there are great benefits to apply this method to treating ancient languages as living languages and learning them that way, I also believe that the method can be applied to learning to read new testament greek, which is a different animal than trying to understand the grammar or syntax ( I have a background in linguistics). I’ve been reading Ephesians 1 and just isolating the prepositional phrases and seeing how these phrases are repeated over and over again, and how, for example certain prepositional phrases are often followed by noun phrases in the Genitive Case. I’m just getting started but I have been through a few courses on Greek Grammar, including one dvd / video class by Daniel Wallace. Have you documented any further phrasal tendencies in the Greek New Testament? Let me know, I’m very interested and thanks for your blog. dpimental

Jamie B

Oops! I saw this on your FB page as posted a few hours ago so I missed that it was 2018 - but if you’re still working on it what I said is relevant, and I’ll be exploring here and on your various channels how it went!

Incidentally, I’m a classical languages person at my core polyglot identity - any advice, since you focus on Arabic, on How to start with Classical Arabic (which would be helpful for my PhD because of the Greek-Arabic-Latin translation programs (Middle Persian in there too in 12-14C Baghdad, Spanish in Toledo) and the Arabic commentary tradition on Aristotle used by many of the Scholastic Latinists. So for now, I want to use modern Arabic dialects (attracted to Egyptian, but would MSA be better for connection to classical or is it more a political and academic bias sell.m, as I suspect?) because there’s a lot more fluency and comprehensible both language learner and authentic material, but my real goal is Classical Arabic. Also just want to do a Semitic language - I’ve had enough with IE languages for now, though branching out into Sanskrit was novel and a bit of a shift at least!

Alex

I’ve noticed a lot of Greek teaching material online uses horrendous pronunciation with the most American sounding verbs possible. I find it difficult to take these teachers seriously. I got a big boost with a series of lessons on Mango Languages which is a paid app. They mainly got me comfortable with the case system, but I feel like I’m still clueless about verbs. Anyway, they teach the language the way you said, like a living language. PS: I always say “forks and knives” and never hear it the other way.

Jillana

Any suggestions for helpful Koine Greek language apps? I’m an absolute beginner and I’m looking for something more enticing than a large text book. Thanks

Robert Rabe

Great Blogs! I have finally found someone who pronounces the Koine using modern Greek pronunciation instead of the classical Erasmanian system, which robs Greek of its euphony! I once asked Bill Mounce if it wouldn’t be a great idea for all seminaries, etc., to go in this direction. He said “yes!” But I don’t think it will happen while we are around.

Robert Rabe

Associate Professor of German, Chapman University

Doug

Great article! I’m a total language neophyte computer professional.

And of course that makes me wonder... will you ever make the files you’ve used for this process available?

Ryder Wishart

This post absolutely nails it.

Once you learn to ‘use’ the language, you can go on to learn about the details. Getting hung up on the details and debates about the details as a first step is not only a recipe for misunderstanding the language, but also for misunderstanding language itself—you start to think all languages but your own native one work like secret codes needing to be broken.

Ailey

Interesting because, many people would say, someone forgets a language because they stopped using it frequently. Like Math in H.S. (Algebra etc.). If you don’t use it enough you lose it. What’s your theory to that Donovan?

Thanks

Ian Macnair

Very interesting. I totally agree with your comments on traditional ways of teaching Koine. Good work, my friend.

Jed Chandler

This is a very useful site! I was just looking on the net to see if anyone was having the same type of problem with their Greek studies that I’m having. I can’t think in the language or write other than by a crazily elaborate effort of prior grammatical analysis. And then I can’t write anything much at all.

I’m self-taught, via a very grammar-based system which uses only New Testament materials for translation. Nothing at all about the language as a means of communication.

I am a medieval languages person, and I’ve realised that I can write and even (on a good day) think a bit in a language when I’m fairly competent in the modern descendants of that language - Old French because of modern French, Anglo-Saxon and modern English, Old and modern Irish mainly. Latin’s OK too, but that’s because I use it so much and often go to a Latin Mass. But Greek = totally stupid and mindblocked.

So - Yes. This is the problem. ““By Week 12 of this term, we’ll be translating the philosophy of Jacque Derrida.”

I think your approach of learning modern Greek may be the only solution, inevitably a very long path but an interesting one.

I’m wondering if changing from Erasmian to modern Greek pronunciation of Koine would help. It’s what they use in Greek Orthodox churches, after all. Has anyone here transitioned successfully from one pronunciation pattern to another?

Best wishes to you all

Neil Campbell

Hi Donovan - can you comment on the SO in John 3:16 - So/houto(s). Is it like an empahasis - God SO SO SO loved the world........or is it like a transition, in this manner, thus (as the Blue Letter Bble says)? Thanks for your website.

Jamie B

I love your thoughts, Donovan, coming to you as a polyglot and aspiring blogger but a classical philology PhD student by day. I’ve done spoken Latin for several years such that if there were. CEFR scale for it I’d be C1+ - speaking, I’ve had hours-long conversations with friends with whom I don’t share any other common language about mental health, chosen family, gender identity.... what people don’t quite get is that it’s not a party trick or “oh that’s cute but useless” - yeah I love speaking, but really what it does is hyper charge my reading fluency and the nuance of translation. So I can do literary translation, not just the “wording” (verbum ad verbum) “translation” that is really just a comprehension check on the grammar - and I’m also working on Early Modern Latin and reading dozens of pages say of Kepler at a time for my diss - and that would be IMPOSSIBLE without treating the language like any other I’d approach as a polyglot, just with a problem in availability of simpler texts (the Vulgate we have sure, a bit like the patterns in NT Greek for its utility in lexical/collocation methods, but in general it’s all like Shakespeare for an intermediate ESL student - and extensive reading is hard.

Anyway, all to say, I really appreciate the perspective on Koine from someone also in the polyglot world - it’s a hard sell to my department that they should encourage students to focus on fluency and proficiency in how they prep folks for scholarship - they’re really open, but don’t really see the power of these methods.

Incidentally, the Polis Institute (www.polisjerusalem.org) has some interesting online videos and TPRS-type methods, and I found Athenaze (only the Italian edition - the English has too little Greek text) a solid reader in between reading and direct methods. Not pedagogically perfect and I don’t necessarily use it with most students, but as someone who has that strong linguistic and polyglot background it might be quite effective for you - it’s what I used to start to get into Ancient Greek the same ways I was doing Spoken Latin after a Hansen and Quinn, turbo-grammar summer course on the fundamentals.

My April-June language focus is modern Greek in the service of Ancient Greek - there are a few interesting out of print books for that take those who know Ancient Greek through modern Greek highlighting the comparisons and points of strong difference - Nea Hellenika gia tous Philologous - don’t have the author at hand, but maybe an interesting resource. Onward! I’ll be following as I do my own 2020 Greek project!

Josh

Hey Donovan, Thanks for the post! I love you thoughts, and have had many of them myself. I’m in the process of dipping back into Greek this last few weeks, and loving it. Forgot how fun Koine is.

I’m curious, it’s been about 10 months since you wrote this. How have your koine studies go? Are you still studying with the same technique? How has it gone? Any tips or tricks for someone going down basically the same path?

ευχαριστω :)

Josh

Ronald Goetz

I am very curious what Bible translators were saying about Luke 17:34-35 before Bruce Metzger eliminated the two “men” in one bed for the RSV revision. I know that in their translation manuals for Luke, Swellengrebel & Reilig, and Bratcher, offered suggestions. But by then it was safer.

Donovan Nagel

If you’re suggesting that it refers to “two gay men in one bed”, not a chance.

I’d recommend not reading the text through the eyes of a 2018 humanities department and instead consider what a 1st century writer would imply there.

Bob

I’m not qualified to settle the linguistic debate whether there is sexual euphemism here. But I think it’s worth noting that if “lying in bed” and “grinding” ARE used euphemistically here, then we must conclude that this text speaks favorably (or at least neutrally) about same-sex relations. After all, in each pairing one person is taken and the other is left. Both people are engaged in the same (presumably sexual) behavior at the moment of the Son of Man’s coming, but their fates differ. That difference must be on account of some other measure than their mutual activity in that fateful moment. It’s fascinating to imagine Jesus describing a gay and a lesbian couple intimately embracing on the last day, and being chosen or not based on something completely other than their sexuality... but it seems much more likely that these words are being used in an ordinary, literal sense.

Brett Hancock

Χαῖρετε Πάντες

Συμφώνω μέτα σοῦ, ἐν τουτῶ τρόπω ἐγω μανθἀνω τήν έλληνικαν γλῶσσαν παλαιάν. (I agree with you, in this way, I study the ancient greek language).

I have taken some Summery classes with Polis Institute, whose claim to fame is treating ancient languages as a Living Language. Now I am taking some tutorial sessions with a spectacular Tutor who graduated from Polis named Roger Toledo (Ρογηρος Τολεδο). The conversation in this, having to describe everything, discuss everything, explain everything in Koine Greek, write everything etc, gets your mind immersed in the necessary repetition that makes your mind grab hold of the language. Then, as you said, I agree, layering on top of that, the necessary grammatical instruction that will lead to proper theological conclusions and not miss the mark so to speak due to only having an approximate understanding you might have begun with in the beginning stages of conversational Koine, can continue from that foundation. It is analogous to a boat, once it is moving, it is so much easier to steer. Great podcast! Lord bless your efforts.

Ἔρρωσο ὦ φιλε

Brett Hancock

simos megalos

Great article Mr. Donovan Nagel!

I generally agree with your arguments. My version of solution for faster learning koine Greek is called audible interlinear multimedia text. Please check it out:

https://greek.red/b/kataivannhnarxaiokeimeno01

Ben

For those interested in learning Koine Greek like a living language, I have developed some audio/visual material on my website here:

www.KaineDiatheke.com

I use the restored Koine pronunciation that Randall Buth and the Biblical Language Center use.

Joseph

So is there a place you recommend to learn koine greek with this method you just detailed? I like your theory but not sure how to put it into practice.

Robert Griffin

Donovan,

Some thirty years ago I wanted to put together a mini-course combining Koiné with those modern Greek terms for things which didn’t exist when folks spoke Koiné. This would allow Greek students to discuss meeting for kafes at a local estiatorio. So far I haven’t found anyone else really interested, but if you (or others) are interested, please contact me.

Thanks,

Bob Griffin

Rev. Fr. Robert Bower

Donovan,

Interesting approach to Koine Greek.

Learning or should I say trying to learn Koine Greek in a 10 week crash course as my first class at seminary was not overly successful.

I have never been able to really read the NT in Greek it has always been dissecting passages with a large set of tools at my side.

I hope with your approach maybe I can actually read the the NT in Greek rather than just dissect it.

I learned Erasmian at seminary but am working on using modern pronunciation instead. If you are interested, I found a reading of the NT using modern pronunciation on Youtube with corresponding text, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-BfYa4QM2dc&list=PL40D66708671D260F

There is also a link to mp3 files.

I do have one question were you able to find a Koine Greek dictionary that integrates with LWT? I have found several put none that integrates well with LWT.

Thanks again.

Bob

This is not as “good” of a grammar as I would like, but for a more functional approach to Koine Greek, I would like to suggest Dobson’s “Learn New Testament Greek” ISBN-13: 978-080101726

It features dual column pages where you can cover the English one one side while you try to read the Greek on the other side.

Christopher Schneider

Donovan - I admire you returning to learn Koine! Having taken Koine and Hebrew in undergrad, I know the struggle well.

I actually posted this article on Facebook in a really neat group called “Nerdy Language Majors” and it got quite a response from people in the Classics to those who have been involved with the Biblical Language Center. If you’re on Facebook, I would encourage you to check it out!

Donovan Nagel

Thanks, Christopher.

Just had a look. Great group there - lots of useful info and discussions! Appreciate you letting me know about it.

Cam Hamm

Donovan, just in case you are not aware of the materials out there available to acquire Koine Greek, taught as a living language, the Biblical Language Center offers courses, materials, and interesting information on learning Koine and other biblical languages in a spoken environment - acquiring the language in a way similar to how people learn their first language. https://www.biblicallanguagecenter.com/

Donovan Nagel

Looks interesting!

Thanks for the heads up. I’ll check it out.

Richard

A wonderful post, Donovan. I have picked up so much from your postes and website. Thanks, best wishes & I owe you a big beer if we ever meet :)

Trevor Foley

Hello,

My name is Trevor Foley, and I am a missionary in Korea as well as a seminary student.

As I have been involved in my ministry context here as a missionary in South Korea, it came up that it could be beneficial for me to see if I could do self-study electives in two areas as part of my degree program at seminary. The overall idea would be to learn how to translate the Bible as a recorded oral record into modern-day oral storytelling contexts, particularly for the sake of Gospel and Bible storytelling with particular attention to translating not only words, but also original and target cultural nuances in light of cultural and linguistic contexts. The first part of this would be to do foundational study in the cultural and linguistic context of the Bible and Greek language, with attention to its various nuances. The second part of this would be to do foundational study and practice in the skill of storytelling itself, with attention to cultural nuances in my ministry context. This would especially be important for presenting the Bible to illiterate people and children in a way that they can understand and that accurately reproduces the intended meaning. Not only this but I believe it would also be important for presenting the Bible to literate people in a way that touches not only the parts of their understanding that are activated through reading, but also those that are activated through speaking and listening.

I am writing to you mostly in regard to the first part of this project, which would be to study:

- How to speak basics of modern Greek using language learning audiobooks for basic Greek oral understanding [30 hrs] (I have been teaching myself languages using this method since I was 17). This can provide the closest reliable foundation for speaking the Greek of the New Testament. Of course, there are major differences, but some scholars argue that Modern Greek is closer to NT Greek than Modern English is to KJV English.

- The oral structure of the New Testament itself, as well as the oral context and culture in which it was generated (The main resource would be Lee and Scott’s Sound Mapping the New Testament).

- Review of Biblical Greek basics and study of intermediate Biblical Greek (I took two trimesters of Biblical Greek in Bible College, and would be building on that).

Keeping in mind that the point is not written translation (or even translation at all, yet, in the first part of this project) but rather learning to orally reproduce the Koine Greek as naturally as possible for the sake of getting accustomed to identifying the nuances that are especially realized through oral reproduction (repetition, vocal stress for emphasis, etc.), do you think learning modern Greek can serve as a good marble block from which to carve?

I am aware of the stark differences between Koine Greek and modern Greek, but I am mostly looking for an effective way to internalize the closest recorded representation of Koine Greek. Again, my hope is not to learn modern Greek and expect to be able to understand Koine Greek; that would be absurd. My hope is to learn modern Greek, being the closest intact phonological cousin of Koine Greek, and shape things like pronunciation, rhythm, and pitch according to that of Koine Greek, which exist in things like the structure and diacritics of the text.

I have seen some programs out there where people essentially advocate speaking Biblical Greek, but with their native accent. Such programs have their place, but this would be a far cry from these efforts that some have put forth to speak Koine Greek because, in this case, of the recognition that things like pronunciation, rhythm, etc. are not only important to the speaking of the language, but also meaning, analysis, interpretation, and translation.

Do you have any direction, thoughts, or suggestions for me with regard to this?

If you have not dealt much in this area, but are interested in the viability of these ideas, I strongly suggest reading Lee and Scott’s Sound Mapping the New Testament.

Thank you for reading,

Missionary Trevor Foley

Naomi DeHaan

Trevor,

If you want to go to a place that speaks some Greek in Korea, there’s a Greek Orthodox Church in Busan that I went to last year (actually, their service is in Greek, Russian, and Korean). I imagine you could pick some things up by visiting (and maybe they have Greek language classes too).