Much of the advice on this site for language learning can be summed up like this:

Get out there and talk to people. Even if you only know two words – hello and goodbye – it’s enough to get you started.

Fact: books are dead and don’t reflect the living, organic nature of languages that are spoken by real people.

I’m a hold-nothing-back, face-your-fears language and cultural immersion guy.

Grammar rules are something we invented to try and make sense of languages that are forever evolving and breaking those rules.

Ironically, the best language learners are the ones who forget about the rules, stop asking pointless questions and are willing to let the language and culture shape and mold them. It’s foolish to treat a living language the same way as a math problem (if I just work out the formula then I’ll get it).

In fact I’ve said many times over that you absolutely don’t need to study grammar to learn to speak a foreign language and shown how this is possible but today I had a thought:

What if somebody has to learn grammar?

What if we study a course at college that requires us to learn all the rules or we want to learn a language that’s only written (such as a ‘dead’ language)?

There are loads of times where we have no choice and/or speaking with native speakers just isn’t an option.

Since I’m working through Ancient Greek (Koine) grammar at the moment, it’s been a great chance to reflect on my own strategies for making grammar study much easier and more enjoyable.

It can be enjoyable believe it or not!

So if you’re in the same boat learning foreign language grammar then keep reading! This will help you.

Know your own grammar first

What’s an adverb?

What’s a gerund?

Do you even know what a verb is?

It might sound crazy to some people but there are genuinely many many people out there (the majority of people in fact) who don’t know what these things are.

You might be one of them (and there’s no shame in it).

Now imagine the kind of work you’ll have cut out for you when you start a new French class say and the teacher starts using these terms – in French.

Before you even get to the French stuff, you’ll be going mad trying to understand what the grammar actually is.

I’ll never forget seeing a grown man storm out of my Greek class a few years ago literally in tears because it was too much for him.

The crazy thing was that it wasn’t the Greek that stumped him, but the English grammar was so foreign to him that he struggled to make sense of any of it (and he’s a native English speaker!).

I had a brilliant lecturer for Hebrew once who showed me the importance of taking time to acquaint myself with English grammar properly before actually trying to learn the grammar of another language – and this is especially important for people who have been out of school for quite a while and forgotten all the basics.

This is not to say that you need to do some intensive course on English grammar before anything else.

It just means you take a bit of time to familiarize yourself with the concepts so you can relate it to what you already know.

Often all it takes is to see a few examples of a grammar point to have that ‘aha!’ moment.

That way when you come across terms in a new language’s grammar you won’t be scratching your head over the descriptions.

Get a simple, easy-to-read grammar reference in English (or whatever your native language is) and use it to guide you through the foreign language material (this series is my favorite).

Whenever you come across a new grammar point that’s a bit confusing, you’ve got a basic reference on hand to explain it to you in a language you already understand.

Take really really hard stuff and make it really really easy to understand

Never start memorizing a bunch of rules if you’re not 100% sure what they’re for. It’s a waste of time.

Step 1 should always be: grasp the concept.

You won’t always find explanations in an English grammar book because you’ll quite often find grammar in other languages that we don’t have and vice versa.

I’ll give you an example:

Let’s say I’m looking at a chapter in a Greek grammar book on past tense.

The book starts using big words like imperfect and aorist, and suddenly I’m confused as hell because all I understand is the general meaning of past tense – something that happened before now.

I had no idea that there are different kinds or aspects of past tense.

Confusion sets in!

So before I go ahead and start memorizing all the rules of these two aspects of the past tense, I need to clarify for myself what they’re talking about.

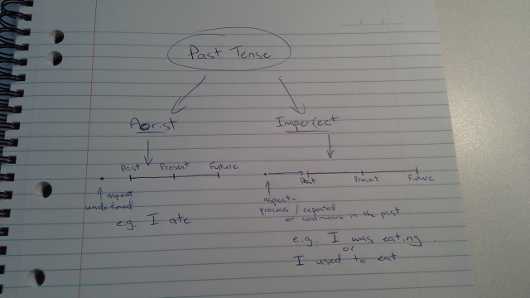

One way that I personally make this hard stuff very plain and simple to understand is by drawing it:

I’ve drawn two branches of past tense and visualized the concept by drawing a basic timeline for each.

The aorist is a simple, undefined past event; it’s something that happened in the past so it’s represented by a a single dot whereas the imperfect was something ongoing in the past so it’s a line with an arrow pointing toward the future.

I’ve taken something abstract and dumbed it down for myself.

It’s a fairly simple image but it clarifies confusing concepts for me and is especially useful for visual-spatial learners like myself who need to see it before it sinks in. I actually didn’t understand this until I had it drawn on paper the way you see here.

Again, I could scribble something to myself to clarify how the past perfect and future perfect tenses in English work:

Remember this is not about being artistic – it’s just a quick scribble to help you see grammar in action.

Now whenever I see these terms in the textbook, I can refer to this to get some better perspective on it.

These drawings might not make sense to anybody else but that’s fine – they’re there to clarify meaning for me and that’s the point.

You could do this in any number of ways – recording yourself explaining the concept in simple terms or writing a quick anecdote that illustrates the point for example.

Also if you find terms confusing then write them down and write in brackets beside them a word or description that makes sense to you personally. For example:

Noun = name.

Verb = doing word.

Adjective = describing word for a noun.

Adverb = describing word for a verb.

Conditional = if.

Conjunction = and, but, or, so…

and so on.

They’re very simple explanations but the important thing is that they make sense to you.

Learn the core, essential stuff first

And don’t necessarily follow a textbook from beginning to end.

Just because a textbook introduces something in chapter 1 doesn’t mean you should start with it. I’ve seen a lot of shitty textbooks that leave the important core stuff till the later chapters and teach unimportant grammar right up front.

Good books won’t do this but in any case you should decide for yourself what’s high priority and what’s not.

I wrote a post a while back called How To Understand At Least 20% Of Every Conversation In A Foreign Language where I talked about the most common 100 words in a language and how understanding them will enable you to understand a huge chunk of everything you hear and read.

These core words in every language are the framework of our conversations – we use them constantly every time we speak.

So make it your priority to identify the words and grammar that are absolutely essential and focus on them first. For example, personal pronouns, conjunctions, basic nouns, verbs and adjectives, prepositions (in, on, under, etc.), and basic verb tenses (past, present and future) definitely should be learned first because you’ll need them straight away.

Be selective about what you learn and only give time to what matters most.

I apply this same principle for learning to speak a language by only devoting my time to the things that I know I’ll use.

Identify patterns and use mnemonic devices to never forget anything

Forget exceptions.

In every language on earth (except constructed languages), you’ll find exceptions to rules.

That’s because languages can’t be bound by rules – we invent rules to help us make sense of things but languages are organic, living and evolving things that don’t like to be told what to do. 🙂

We know in English for example that -ed on the end of a verb indicates past tense but then we come across words like ate, saw, sang, etc. which give a big middle finger to this rule.

So just focus on the patterns of unexceptional grammar, use mnemonic devices to help you remember them and forget exceptions until much later on.

What’s a mnemonic device?

It’s simply a fancy term that means anything that helps you remember something.

So for example in Koine Greek the word for tree is δενδρον (dendron) and it’s an easy one to remember because quite a few trees in English have names that are of Greek origin (e.g. rhododendron).

That’s a mnemonic device for you (albeit an easy one).

The word for death in Greek is θάνατος which I always remember because the bad guy in the cartoon Gargoyles was named Xanatos and death is bad. Xanatos → bad guy → kills people → death → θάνατος.

The same kind of thing can be done with rules and conjugation tables.

Take this table of endings for the present indicative active tense in Greek for example:

The bit that stays the same all the time is the φι- bit at the start which is the root of this particular word meaning to love.

For each one of the endings you could make your own mnemonic devices to help you remember them:

-ω (oh): Ohhhh I love it!

-εις (ice): You love ice.

-ει (eye): He, she, it loves my eye.

-ουμεν (ooh men): ‘Oooh we love men’, said the ladies.

-ειτε (aighte): You’ll all love it, aighte (alright)?.

-ουσιν (ooh sin): Oooh, sin is something they don’t love.

A few of these may seem silly but you’ll never forget them.

The great thing is that for many languages, once you learn a few of these conjugation tables, you start to notice similar patterns in the language for other conjugations.

The best way to really make it sink in and get used to these patterns is the same way you would if you were learning to speak a language – lots of exposure to the target language in context.

Learning rules for words as you encounter them in sentences is a heck of a lot better than simply memorizing them in isolation as single words.

You need to see how words interact with each other in natural sentences.

The only difference is that instead of listening and speaking, you’ll be doing lots of reading and writing to look for these patterns.

I also use and recommend the Shaum’s Outlines if you’re looking for a solid, detailed yet clear (important!) grammar book.

🎓 Cite article

Grab the link to this article

Grab the link to this article![Black Friday (2025) Huge Language Learning Deals [+ Gift Ideas]](/.netlify/images?url=_astro%2Flanguage-learning-gifts.B3xs8tp4.jpg&w=270&h=152&q=50)

5 COMMENTS

NO ADVERTISING. Links will be automatically flagged for moderation.

Artie Duncanson

I’m glad you started this article with the disclaimer that you don’t need to sit down and study the grammar. I was learning a local Filipino language called Cebuano through immersion with the locals, and after a couple of months, certain ways of saying things just sounded wrong to me. I realized later that I was absorbing the grammar.

JorgeSivit

Very good tips. I find learning grammar in our native language first, and making hard staff easy to understand are key. Creating graphics and writing rules and explanations in my own words helps me a lot.

Natalie

Admittedly this is a bit off-topic, but I find it absolutely appalling that some people are completely ignorant of the grammar of their native language. I’m not faulting them, of course—I’m faulting the education systems (and politicians who implement these systems) that allow this to happen! I’ve encountered people from many English-speaking countries, including the US, the UK, and Australia who don’t have the slightest idea what transitive and intransitive verbs are, which I think is crazy!

lecriveuse

i agree! i want to make my own sentences, understand what’s being said to me and not sound like a complete idiot. i got a bachelor’s in french, and i had to learn grammar. it helped me with english, too. it’s just plain lazy and trifling to not want to learn grammar! some don’t care to read or think. if they can’t be spoon fed or watch a video, they’re in a crisis.

Enrique Espinosa

Very Good Donovan!